Students as Questioners : What is a Question?

Students as Questioners : What is a Question?

Questions. We ask them when we need directions. We ask them when we don’t understand. Sometimes we ask questions in outrage, other times we ask them in curiosity and wonder. Sometimes questions are rhetorical, other times they are urgent. If we want to help students be questioners, we need to help them understand the types and purposes of questions and ways to use questions effectively. For the next few weeks I’ll be examining models of student questioning and how they can be used to help students develop both understanding and creativity.

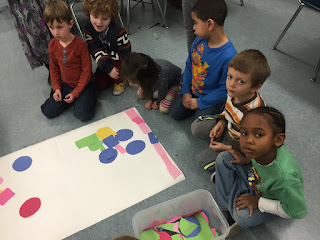

First and most basically, we need to teach students what a question is. Very young children, as all kindergarten teachers know, have trouble understanding the difference between a story and a question. Without guidance, a suggestion that young children ask questions of a visiting firefighter can result in long stories about vaguely fire-related events. Early childhood educators are accustomed to helping students discern the difference. But that is not the only area for potential confusion.

Less common is any effort to help students understand the difference between genuine questions and checks for understanding. Teachers ask a lot of “questions” to which they already know the answer. As teachers, we understand this as an important part of our formative assessment processes. We ask students to restate information, give examples, or solve problems as a way to determine how they understand content. The problem is, when we call these queries “questions” (and particularly if they are the only type of question students experience in school), we teach an unintended message. Students can come to believe that, at least in school, questions have one correct answer and the teacher knows it. Their goal, under such circumstances, is to determine what the teacher is thinking and replicate that “answer.” Such interactions bear little resemblance to the roles questioning plays in the real world, at least outside game shows.

Of course checks for understanding play an important role in school and, in fact, formative assessment is important in building a classroom atmosphere in which creativity can thrive. It simply is not the same as asking a genuine question. So why not teach students the difference? We can honestly say to young people, “You know, many times I ask questions in class and I already know they answers. When I do that, I’m trying to find out what you know and figure out how best to teach you. I need to check your understanding to make sure we are ready to go to the next idea. But that’s not the same as a real question. When I ask a real question, I’m wondering about something and I don’t know the answer. Sometimes there is no right answer at all!”

If we do this, we can (at least sometimes) frame our interactions so that students can identify the differences in purpose. A teacher might say, “OK, let me check to see if you understand,” clearly signaling a particular goal. It is also possible to help students identify processes to check their own understanding. The teacher might suggest, “This is a good time for you to check to see if you understand. Is there something you’d like to clarify? You might want to ask a question about something that was unclear, or try giving an example to see if it is correct. Sometimes, when I want to check my own understanding, I say to someone, ‘Let me see if I understand. Did you mean. . . . ?’ Raphael, what might you say to me to check your understanding of this diagram?”

Other times questioning might have a different goal. The teacher might say things like, “Lately, I’ve been reading a lot in the paper about the unusual algae growth in our lake this year. I have a lot of questions about that. Do you? For example, I’ve been wondering if this is a new kind of algae, or just more algae. I don’t know and I’d like to find out. “ This could lead to a discussion about what the students know about the local situation and what genuine questions it raises. The lesson here is quite different: questions can be used to express curiosity and guide us in seeking information.

As students begin to understand that things phrased as questions can have very different purposes, they can begin to use questions strategically. Next we will be working on teaching students to ask their own questions.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for taking the time to comment.